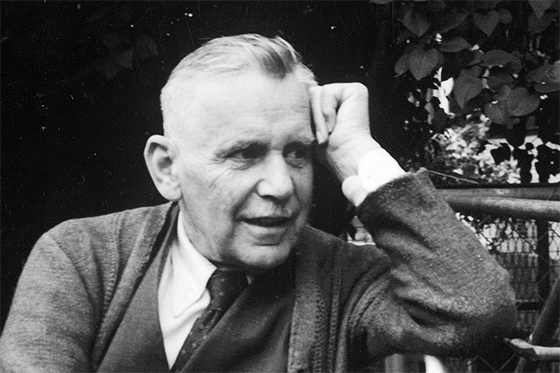

Bild: Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Biography

> Deutsch

The composer Othmar Schoeck was born in Brunnen on 1 September 1886, the fourth and youngest son of Alfred Schoeck, a landscape painter, and Agathe Schoeck-Fassbind, the daughter of a local hotelier. Together with his three brothers Paul, Ralph and Walter, Othmar grew up in the Villa Eden built by their father (today the Villa Schoeck), and all four looked back on their childhood in Brunnen as an idyllic time. Othmar studied at the Zurich Conservatory under Friedrich Hegar, then later at the Leipzig Conservatory under Max Reger. He thereafter settled in Zurich, where he worked variously as a composer, piano accompanist and conductor. For 27 years he also worked as the Chief Conductor of the City Orchestra of St. Gallen.

In 1916, Schoeck made the acquaintance of Werner Reinhart, a businessman from nearby Winterthur whose love of music was exceeded only by his wealth. Over the ensuing decades, Reinhart provided financial support for numerous Swiss and Central European composers ranging from Igor Stravinsky (whose Soldier’s Tale he funded) to Alban Berg, Arthur Honegger, Ernst Krenek and others. Reinhart also provided assistance to writers including Rainer Maria Rilke. But the artist to whom he gave the most extensive, long-lasting support was Schoeck. Shortly after they met, Reinhart began paying Schoeck a quarterly stipend that was continued by his heirs after his own death in 1951.

During the 1920s, Schoeck’s reputation grew both in Switzerland and in Germany, and his works were performed by leading conductors such as Wilhelm Furtwängler, Fritz Busch and Karl Böhm. From Penthesilea (1927) onwards, his operas were given their first performances at leading German opera houses. Ample documentary evidence exists to prove that Schoeck had no fondness for Hitler’s Germany and its racist policies, but nor did he make any concerted effort to distance himself when the Nazi authorities courted him throughout the 1930s and the early 1940s. He still earned most of his royalties from Germany and accepted offers for the world premières of his operas Massimilla Doni in Dresden in 1937 and Das Schloss Dürande in Berlin in 1943. He was even flattered into accepting the tainted Erwin von Steinbach Prize in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1937. Schoeck believed that remaining silent on politics in Germany would suffice to absolve him of any hint of collusion, but he was proven dreadfully wrong. His inability to cope with the conflict that thereby arose, both external and internal, led inexorably to his physical and mental collapse in spring 1944 – a crisis from which his health never properly recovered.

Schoeck was still a semi-invalid in the summer of 1945 when the little house in Zurich he had rented for the past thirteen years was put up for sale, which would have meant packing up all his belongings and hunting for a new abode with his wife and young daughter. But Werner Reinhart stepped in, bought the house, and promptly handed it to Schoeck as a gift.

Schoeck’s final years were marked by dwindling health and feelings of isolation and aesthetic estrangement in the face of the post-War avant-garde (and this despite the advocacy of performers such as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau). Schoeck died of a heart attack in Zurich on 8 March 1957. After his death, his works received little attention until the 1980s. Since then, however, his songs have been recorded complete, as have almost all his operas. Artists such as Christian Gerhaher and Heinz Holliger have performed his major song cycles, and his reputation has also spread to the Anglo-Saxon world, where his staunchest adherents include Alex Ross, the award-winning author and critic of the New Yorker, and the conductor, author and President of Bard College Leon Botstein.

The Othmar Schoeck Festival was founded in Brunnen in 2016 and has been an annual event since 2020. It aims to place Schoeck’s music on a secure footing on the Swiss and international scene while engaging critically with his biography and works here, in the place of his birth.

Author: Chris Walton